Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art – Ends 16 March 2025 – Free

A short history of Franki Raffles and her life in retrospective

Franki Raffles (1955-1994) contributed a lot to both the field of photography and to female art during her relatively short lifetime; she passed away during childbirth aged just 39. Her career emerged in the late seventies and early eighties just at a time when feminist theories were gripping the art critical world in a way they had never done so before. This gave her the stable ground upon which she could build a body of work embracing the female, femininity and show the world as viewed from a female perspective. As Scott and Brownrigg quoted from Raffle’s own notes, “Most of my time is spent talking to women about the issues to be portrayed. Without the understanding that I gain from talking to women, I cannot produce good photographs.” (1); this statement centres Raffles creative output as something which emerges from ideas of community and possible sisterhood rather than being a disparate series of photographs which have been placed together only because they are judged to be aesthetically pleasing.

Raffles first became interested in photography while she lived on the isle of Lewis, Scotland in her early twenties, she used this medium to document the working and living conditions of the local women within traditional crofting community where she had made her home. (2) After this, Raffles was actively sought out and commissioned for photographic projects. Shad images published in local authority literature, NHS recruitment material as well as holding exhibitions throughout the entire span of her short career. During the mid to late 1980’s Raffles used her photography as an instrument of demonstration and social documentary, this included photographing such things as the poll tax protests in 1984. In 1989, she held an exhibition called To Let You Understand, this exhibition shone a light on some of the work which women are expected to do, both in and out of the home. This exhibition included images of women in varying positions, almost all low paid and most physical, or domestic style labour of some kind, one image even demonstrated the structural misogyny that would have been prevalent within many of the workplaces and institutions at the time. (3) During this part of her career, she took part in creating a campaign called Zero Tolerance’ which was a campaign aimed at reducing the domestic violence which women and children regularly suffered and which men viewed as being an ordinary part of home life at the time.

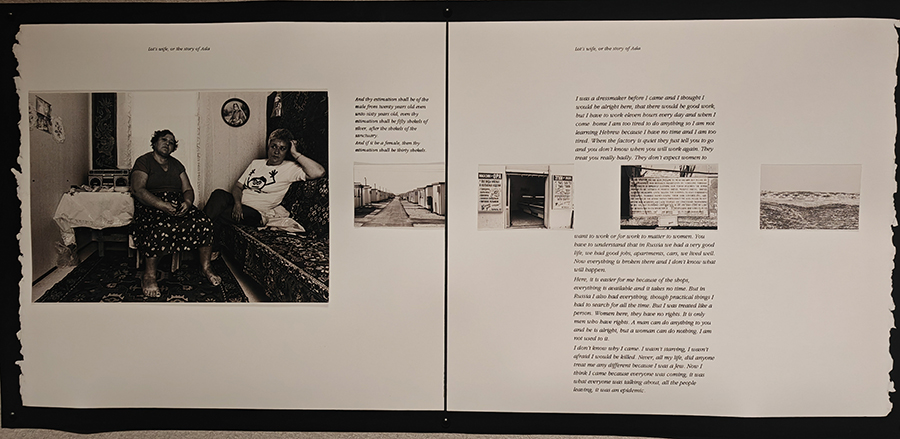

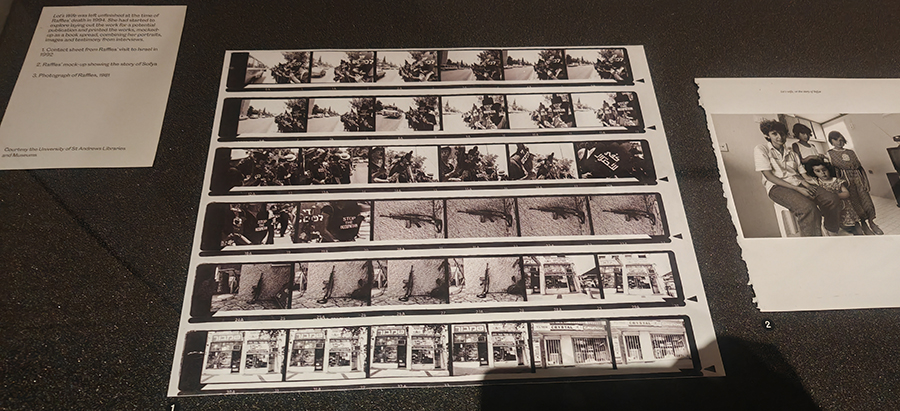

Her later work, particularly in the Soviet Union and then in Israel after the fall of the Iron Curtain, dealt with themes such as migration and resettlement as well as building on her previous body of images on female experience. In her unfinished project Lot’s Wife, she spent time discussing the effects of moving between places and resettling in the new country and culture demonstrating how this interacted with the primary issue – that of being a woman, and also with the expectation of what women do within society. As a photographer who had a Jewish ancestry, I can’t help but imagine that this would have been a project close to Raffles heart, a way perhaps for her to discuss the very real situations and struggles which emerged with the coming together of the Jewish Diaspora as those from the USSR relocated into a modern, westernised Israel. Although Raffles passed away during the time in which she was producing this particular body of work, she left behind copious notes which have been utilised to understand her workflow at the time, leading to an understanding of how she was wishing to portray this project to the public through the aegis of exhibition.

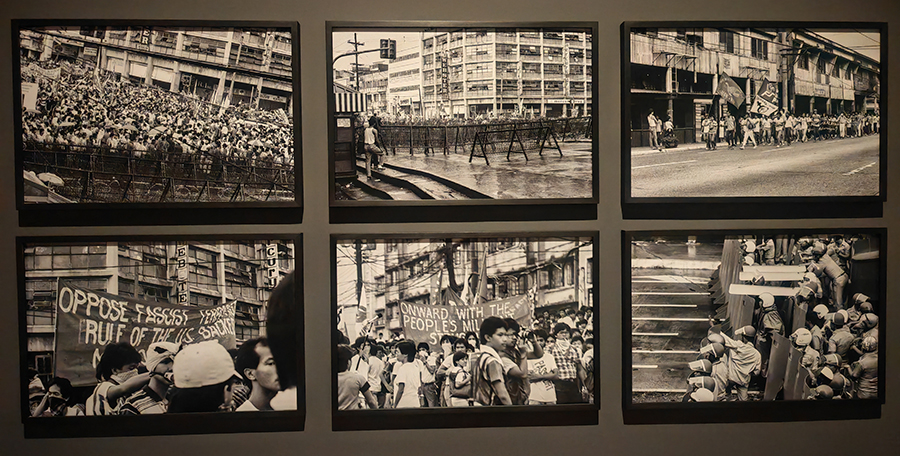

The exhibition Franki Raffles: Photography, Activism, Campaign Works is currently being displayed on level three in the Baltic Centre For Contemporary Art in Gateshead, with the exhibition itself sprawling throughout the large gallery space on that floor. The exhibition space itself is divided into three main sections, each of which highlights a different portion of her life and career as a photographer and activist. As you enter the gallery, you come face to face with a photograph of Franki Raffles herself, as well as some of her early photography from the Isle of Lewis. There are also images from a project she shot in some of the most deprived areas of Scotland’s central belt. The space beyond this contains images shot as part of her exhibition work for Soviet Women, To Let You Understand, Women Workers, and also her Sisterhood Solidarity exhibition which highlighted that what is considered to be female work is generally the similar globally; this series of pictures was shot in China and Tibet. The final area of the gallery highlights Franki’s work documenting protest and campaigning, it contains a small space on disability inclusion, an exhibition of photography of protesters from the 1984 poll tax protests, and an overview of the Zero Tolerance. Lastly, a display of the project she was working on when passed away, Lot’s Wife, which has been displayed how researchers think she would have wanted it displayed.

The first thing that you see when the lift doors open on the third floor of the gallery is a huge photographic contact sheet, one which has been blown up to fill the entire wall space. In a sense, this oversize, awe inspiring piece of photographic history highlights the huge professional stature of the photographer whose work is displayed inside. The space immediately inside the gallery is relatively dark in comparison to outside, there are pools of brighter light shining onto the walls which contain her photography, with the remainder of the wall unlit. This is quite an interesting method of lighting in which the pools of light surrounding individual sets and groupings of photographs highlights that these form a single body of work, and therefore should be viewed and interpreted as a whole, rather than as individual photographs.

On the wall opposite to the contextual information about Franki Raffles, there are shots from two of her earliest bodies of work. Each of these sets of work are placed separately, with a little information about the context in which the images were taken. There are only nine photographs in the section on Lewis, but between them, they illustrate a story of the working life of women on the island. The images show work out in the fields with the sheep, one lady even using a manual hand scissor to shear a sheep. This would have been a tough job for most people and would certainly have destroyed the view of island life as being an easy life within a scenic idyll. Raffles didn’t just show the working conditions either, there is a picture with a run-down house that has a boarded window; this picture isn’t saying that all housing on Lewis was in this state but suggests that the condition of housing here has generally less cared for.

As can be seen from the other set of images in this area of the gallery, Lewis didn’t have a monopoly on run down housing stock. In scenes from her exhibition Who’s Holding the Baby (1978) we see dilapidated housing estates, children playing – often without anything to play on, and scenes of urban desolation caused by an architectural style which was at odds with family life. This was a series which was created to highlight the barriers to work for women of the time, as well as showcasing the oppression of the lower classes within society through providing them with low quality work and housing within Scottland’s cities.

Raffles photography in the late nineteen eighties became almost exclusively about the female experience in society and how this experience differed from the perceived experience of the male. Her exhibition To Let You Understand was created between 1987 and 1988 and exhibited both in Scotland and also in Russia when Raffles went to shoot a project over there. The way it is exhibited is mirrors the exhibition of Russian Women on the opposing wall of the gallery space; huge walls of aggregated photographs with no information at all about their content or context. This method of display, while seeming a little strange within a major retrospective exhibition, really gives an impression of the quantity of work which went into Raffles projects.

At first this lack of contextual information is a little irksome, you look up at these walls of pictures and you ask yourself, Who I she? Does she enjoy this work? Why is she doing this work? Some of the work the women pictured are doing appears incredibly laborious and difficult as well as being boring and low quality and poorly renumerated. However, there is a small board opposite each wall of photography which contains a handful of examples of photography alongside statements given by the women in the pictures which were recorded by Raffles in her notes and diaries. These bodies of work are interesting in themselves and are worthy of taking time to appreciate. Especially considering the difficulties that Raffles must have had in accessing all of these different spaces, within different organisations and within different countries, she has curated a marvellous collection of work.

While we know that Franki Raffles travelled to Rostov, in Russia; and also, Georgia to shoot her Russian Women project, however there is nothing within the exhibition which tell us what shots were taken at any specific location. This, in my opinion, is where the style of exhibition which has been utilised for Raffles work falls short. Much of her work it is left partially uncontextualized leaving the viewer a little uninformed as to how these photographs properly fit into the body of work itself. There appears to be a greater range and variety in the types of work, which was being done by the women in Russia, then what women in Scotland were able or willing to do, this is an interesting look at how different societies value these roles and the abilities of women. The one thing that Raffles noticed never changed no matter the society she was in was that women were almost always the primary caregivers for children and almost exclusively had the responsibility for most of the work within the home as well as doing their own job too.

The very rear third of the gallery space is dedicated to Raffles campaign work for social change as well as a couple of photographic projects she created under the aegis of using photography as a tool of protest and societal change. There is a display of photographs and advertising material which comes from the campaign Zero Tolerance in the mid 1980’s; this was a campaign which was designed as a tool to use societal pressure to try to end the rampant domestic violence which women suffered at the time. There are pictures of billboards and advertising spaces within this part of the exhibition which help to contextualise the locations in which these materials were originally displayed as well as the content of the posters themselves.

Raffles, during the eighties was engaged in trying to document what was going on in society, this included of course the protests that were taking place when the then Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher attempted to introduce a Poll Tax. This was seen throughout the country as a regressive tax and one which would take money from the poorest in society. Therefore, it was met with protests throughout the country. She worked to show the people who were demonstrating, highlighting the protests as a social issue and presented them in a different format back to society for the viewing public to reflect on. This type of documentary photography holds an important position within the genre as it provides a literal snapshot of any civil strife as it happens, placing it into a context immediately accessible by those viewing in the future.

The final part of this exhibition, and the final project Raffles was involved in at the time that she passed away was Lot’s Wife. This is only a small part of the overall exhibition, showcasing Jewish women who have moved from a post-soviet Russia to Israel, to the promised homeland for their people. This project has been displayed in the manner that it was thought Raffles would have wished it displayed through examination of her copious notes.

Lot’s Wife examines the lives of several Russian Jewish women as they relocated to new accommodation in Israel and follows how they sought to adjust to their new lives and circumstances there. This project contains not only photographs but also extracts and accounts from the notes which Raffles took as she interviewed these women. Her aim was to highlight some of the many issues which women have as they migrate between different societies; and to contextualise these against the things that remained the static for most women globally.

Centrally within the gallery itself, the curators have included a study space with an assortment of tables and books, encouraging the viewer to come on in and read about feminism and the feminist perspective in art which is the ‘lens’ through which Raffles has framed her entire oeuvre. This is a great touch as it enables all those visiting to have a look at various texts which may enable them to better see the exhibition as Raffles created it; through the eyes of feminism.

I felt that he exhibition as a whole is a great retrospective of Raffles life’s work; however, the gallery curators could have done a little more to signpost a route around the exhibition so that her work is viewed as per her timeline. On the first visit I made to this exhibition, it wasn’t obvious to me which route around the gallery would be the most beneficial. The exhibition itself though is a high-quality offering with a lot of content, though it could have done with being better contextualised, this could have been done digitally so that it didn’t break the flow of her work. This is an exhibition which I will be back to look at again during its running time, which is until March of 2025.

- Scott, Alistair; Brownrigg, Jenny – ‘Observing Women At Work’: Franki Raffles

- Heeley, Lydia Isabel, 2019, Scottish Documentary Photography And The Archive: George M. Cowie, Franki Raffles And Document Scotland In The University Of St Andrews Photographic Collection P.67 http://hdl.handle.net/10023/18364

- Spencer, Catherine, 2022 To Let You Understand: Franki Raffles, Photography and Feminist Society, ‘Art History’ Vol. 45, No. 3, pp 624-629 DOI:10.1111/1467-8365.12661

Links

https://baltic.art/whats-on/02-franki-rafflesphotography-activism-campaign-works/

https://archive.org/details/desperatelyseeki0000unse_b4v2/page/6/mode/2up?q=Franki+Raffles

https://archive.org/details/womencontemporar0000unse/page/108/mode/2up?q=Franki+Raffles

https://archive.org/details/famousrectorsofs0000unse/page/108/mode/2up?q=Franki+Raffles

Again, a marvellous report on an art exhibition. I also visited this venue to see it for myself. It was interesting and much remained in my thoughts partiularly the photo of a rundown russian building where flower boxes had been hung from the windows to cheer things up. Showing that women always try to brighten and improve their surroundings. However, some photos seemed harsh but illuminating, partcularly a pair of women plastering and many doing what previously would have been considered male employ, especially in the period it was taken comparing the equality of women in the workplace in Russia compared with that of the west. However, I think Miss Raffles must have had some kind of trauma with men in her younger days as it appears she had nothing good to say about the male gender. However, regardless of that, it is refreshing to find a female artist using the medium of photography to highight global social injustices and attempting to highlight and improve upon them.

LikeLike