Laing Art Gallery. 27th May -14th October 2023.

The Essence of Nature is the current paid exhibition taking place in the Laing Gallery, this exhibition is one that I have so far avoided going to as it contains two distinct styles of art, Pre-Raphaelism and Impressionism. I am not a fan of the latter style. The ticket price of £8 for a single visit ticket isn’t overly expensive, especially when considering the amount of work that has been done to bring artwork from quite a number of different collections into one place, especially for the exhibition.

There is one thing that I found very irksome, that is the lack of any guide or exhibition catalogue to accompany the exhibition. This means that the voice of the curatorial team is lost to the casual viewer and that we will never really know what was behind the staging of this interesting exhibition. It also means that anyone who likes the exhibition will be unable to look back at it through the exhibition guide in future years. This to me is a major omission by the gallery and their curatorial team, one which I hope they don’t repeat at future exhibitions. The Laing is also the only major city gallery these days that doesn’t permit taking photographs of artworks for personal use, or personal record, which combined with the lack of any guide book makes it almost impossible to recall what was hung at this exhibition at a later date.

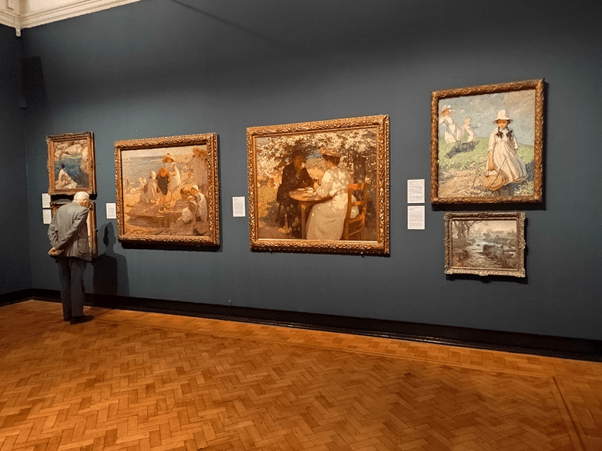

Once inside, the exhibition begins with the usual preamble about the exhibition, and about the aims of the Pre-Raphaelites with their artwork and intentions; there is a second wall at the start of the Impressionist section with a little about their group too. The exhibition itself is divided into two galleries, the first gallery is Pre-Raphaelite, the second exhibition gallery is English Impressionists and a few other artists which don’t appear to fit into either grouping.

As the exhibition is titled “The Essence of Nature”, it’s a good assumption that the majority of the images on display will be images of nature and natural scenes in some way; to begin with, the exhibition lives right up to this assumption. The first image that I saw that really drew me in was John Ruskin’s Spray of Dead Oak Leaves (1879), which to me looked a particularly good imitation of a natural twig with dead leaves on it. Ruskin’s tone, colouring and even the apparent texture that the eye can see were pretty accurate. For me personally, I felt it a great opportunity to see one of Ruskin’s personally drawn works in its finished state. I don’t often come across Ruskin’s artwork and the best previous example I had seen of how he paints was his Cornflower at Wallington Hall which he left unfinished – he got into a bad mood after being informed that he was painting the wrong flower. It’s still unfinished on one of the pillars in the central hall to this day.

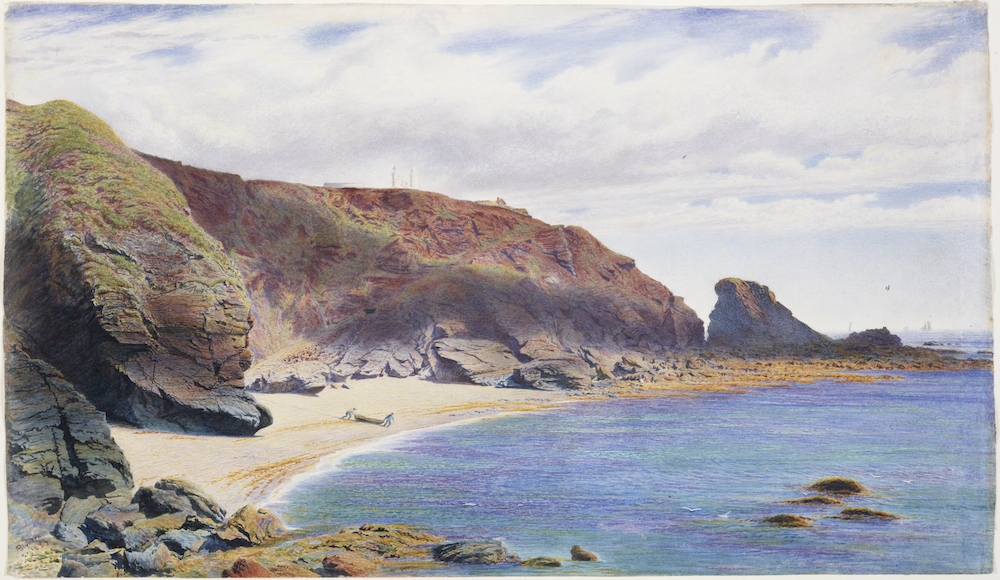

As I moved around the gallery, I came to a wall which held a few interesting landscapes, what caught my attention was the way in which they appeared to demonstrate a progression through time as well as a progression of artists and their skills. Of the four, three were large landscapes painted in a quite compact format, the fourth was a Cornish seaside scene with many of the same qualities as the others. William Holman Hunt’s Plain of Rephaim from Zion (1855), John Ruskin’s Mer de Glacé, Chamonix, France (1863), and John Brett’s Etna from Taormina, Sicily (1870), are all wide-open landscapes with an allusion to contain a huge area of space, yet they present it in an easily identifiable and readable way for the general viewer of these paintings. Ruskin and Brett especially had a great spacial progression and an excellent use of artistic devices like atmospheric perspective to offer that extra sense of depth that was needed within the more distant parts of the picture space.

The level of detail within these three artists’ landscapes is equally matched by that of the fourth on this wall, View near the Lizard: Polpeor Beach (1862) by Anne Blunden. Her scene is much smaller in both scale, composition and terms of the sheer area that she wished to portray, however, that which she has painted is as detailed, intense, and colour-rich and has a similar level of charm, though in a more homely sense than do their works. Blunden’s painting of natural scenes was something that Ruskin had encouraged. He encouraged and instructed several other women who either belonged to or were close to the Pre-Raphaelite circle with very mixed results. Blunden’s painting may also be smaller than those of the male landscapers as she was female, so was required by society to paint on an easel, rather than on great boards that would require carrying around.

Aside from Blunden, William Bell Scott, and Charles Napier Hemy also painted competent beach scenes. Bell Scott’s Seascape on the Northumbrian Coast (1863) beautifully demonstrates the austere beauty of a Northumbrian sunrise through his use of pastel pinks and blues, The rocks are painted with enough detail that you can almost imagine touching them. Charles Napier Hemy’s Under the Breakwater (1863) on the other hand is a much tighter scene, with an ageing and heavily shored-up breakwater taking up most of the picture space. Hemy appears to be using an aesthetic of ruination which was relatively popular in Victorian times. There is what appears to be an adult and child enjoying the beach behind the breakwater, which looks to be in such a ruinous state that it could collapse in a stiff breeze. At this point in the exhibition, it is nice to see some man-made objects and people casually being blended unobtrusively into some of these scenes.

Albert Goodwin’s Whitby Abbey (1910) captured my interest as he framed a scene that has great familiarity as many contemporary photographers like to frame the abbey ruins with the lake in the same manner. The way it has been captured here though was just very atmospheric. This interaction of the human and nature can best be seen in this exhibition through the aegis of Ebenezer Downard’s A Mountain Path at Capel Curig, Wales (1860), which is a painting in which most of the background has been closed off by an outcropping of rock and the rise of a hill, with the exception of a corner where it has been revealed as a mountainous place. Within this scene, a woman is taking hay and water down to some sheep on the hills, there is a sheep following her. The lady is walking on a footpath that looks every bit as worn and erosion suffering as those in that region of Wales do today. The placement of the farmwoman is extremely well-balanced with a foxglove in another corner. The painting September (1915) by Edmund Blair Leighton is a fantastic example of what Pre-Raphaelitism is supposed to be, he is telling us the full story, rather than leaving out the small details that clutter the scene like, for example, the laundry basket under the line, and the apple gathering baskets which are strewn around the orchard in a haphazard manner. Leighton has seen fit to include these in his overall account of the scene which serves to inform us that this is a scene of feminine domestic work, taking place in an idyllic countryside setting.

My final comment on the Pre-Raphaelite side of this exhibition is Frederick Sandy’s Valkyrie (1862), which stands out as the most obvious Pre-Raphaelite picture within the display. Its subject, that of a woman who is either capable and independent, or of a woman who is thought to have occult powers; is pushed to the fore. Standing there wrapped in a shawl, ginger hair flying in the wind, staring a raven directly in the eye, with a single foot on the scull of a long-dead individual, she has the air and appearance of a woman who is able to do anything she desires. The entire picture space around her has also been filled with a bough for the raven to sit on, irises and other flowers by her feet, the background to this scene is only glimpsed in between the other foreground elements.

As I moved along into the second part of the exhibition it was noticeable that the paintings here have a completely different feel to them. They tend to be slightly larger in format than the previous arrangement and their style has changed, these are Impressionist, using larger brushstrokes, concentrating less on the detail and more on the overall picture that they are creating. Unlike the Pre-Raphaelites, most of which were totally natural scenes, the British Impressionists selected for this exhibition have mostly nature scenes that contain people within them as opposed to completely natural views. Their painting style is also much different with a fair few artists choosing to utilise larger brush strokes over the fine delineation of detail which was used in much of the art of most preceding groups.

Thomas Sheards Harvesters Resting (1898) is the first work in this section that actually took my breath away, its quite large size at 146 x 200 CM allows Sheards to include a lot of small details within the scene. Whilst this is ostensibly a scene of the British countryside, in actuality it is a scene of countryside life. The picture’s subject matter is the harvesting team resting at the end of a hard day’s physical labour in the sun rather than the overall image of a late afternoon. The sunlight can be seen slanting in at an angle illuminating the edges of the stocks of wheat which take up a large portion of the background of the scene here. The tone of the painting suggests warmth, homeliness, and tradition as it idealises the act of bringing in a harvest through hard labour. A complete contrast to Sheards’ work is that of John Young-Hunter who’s painting The Midday Meal (1895) which has been included amongst the impressionists. This artwork appears at first glance to be closer in similarity to pre-Raphaelism in its context and honesty of scene but has a definite impressionist feel in the details. The scene itself is interesting as there appears to be a lady towards the top of a path, leading calves down the hill to where one is eating from a bucket, the entire depiction takes place within a relatively shallow picture space with quite a steep recession into the distance created the further one goes up the canvas. This recession effect is not unlike that found in old Dutch paintings.

When I imagine an idyllic British countryside scene of a bygone era, Stapleford Church (1952) by Margaret Fisher Prout fits comfortably into this mental picture, as does Samuel Birch’s The Morning Mist (1938). Both of these paintings, though in vastly different styles demonstrate qualities of quintessential Britishness. Prout has placed a small stream in the foreground, with a church and churchyard further back into the picture space, this could be an allusion to it being a village green. Birch’s picture on the other hand contains a river flowing towards the viewer, a traditional stone wall, and trees to one side and a cottage hiding slightly in the mist at the other. Both of these images radiate the timeless ideal of a place within an idyllic countryside estate or village.

Overall, I felt that this exhibition was trying hard to be something it just couldn’t be. It is implicit from the title of the exhibition “Essence of Nature” that the central focus of the exhibition should be nature; however, the displayed artwork just didn’t match the title. There were numerous examples where nature was not the focus of the art, sometimes it was used as a backdrop, and others it wasn’t actually present at all. Several pictures showed people or places as a part of the natural environment, but that I really down to artistic interpretation of the subject than it is to being a reality.

The use of two distinctly different art styles whose periods of usage overlapped was intriguing but then caused a jarring sensation as you moved between making it appear that two separate exhibitions had been combined. Perhaps if the art had been displayed thematically by subject matter, placing Pre-Raphaelite artworks side to side with those of the impressionists and moving through the exhibition by content, the exhibition could have been more cohesive and easier to view.

All in all, I feel that this was a reasonable exhibition; for a small local gallery, the Laing did really well in securing loans of very competent artwork to display within the city however, it does fall short when compared to exhibitions like “The Legend of King Arthur: A Pre-Raphaelite Love story” which was staged locally at Tullie House in Carlisle a few months ago. One again, I must state that not having an exhibition catalogue for this exhibition is a huge loss as it would have made a wonderful way to remember this exhibition in the future.

If you have enjoyed reading this blog, why not help support my work by buying me a coffee. https://www.buymeacoffee.com/aislingonart

References

Wallington central hall flower-painted pillars https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/585694

Pamela Gerrish Nunn, Victorian Women Artists, 1897

Links to mentioned artworks

https://victorianweb.org/painting/ruskin/wc/96.html

https://www.nationaltrustcollections.org.uk/object/585694

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/mer-de-glace-in-moonlight-chamonix-262095

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/mount-etna-from-taormina-sicily-71694

https://victorianweb.org/victorian/painting/blunden/2.html

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/seascape-on-the-northumbrian-coast-135424

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/under-the-breakwater-37200

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/whitby-abbey-north-yorkshire-40020

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/a-mountain-path-at-capel-curig-wales-198586

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/september-36904

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/valkyrie-67761

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/valkyrie-67761

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/harvesters-resting-36138

https://artuk.org/discover/artworks/the-midday-meal-35545

Links to Gallery Exhibition websites

https://laingartgallery.org.uk/whats-on/essence-of-nature

https://tullie.org.uk/events/the-legend-of-king-arthur-a-pre-raphaelite-love-story/